How Drug Checking Could Prevent Fentanyl Overdoses

Drug checking offers a public health approach to the fentanyl crisis.

From 2013 to 2016, deaths from fentanyl rose more than fivefold to about 20,000.

Dealers have increasingly laced street drugs with fentanyl, which is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, creating the potential for fentanyl overdose among people who don’t even know they’ve taken it.

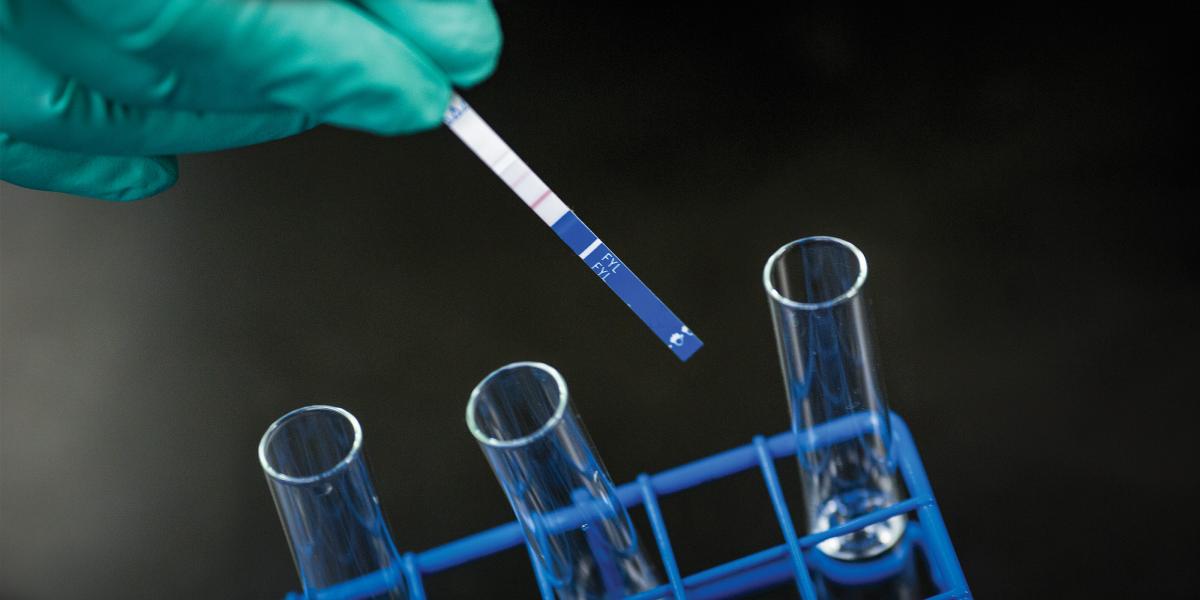

The Fentanyl Overdose Reduction Checking Analysis Study (FORECAST) found an effective, inexpensive way to alert people who use drugs to the presence of fentanyl. With support from the Bloomberg American Health Initiative, researchers from the Bloomberg School and Rhode Island Hospital/Brown University found that fentanyl-testing strips, which cost $1 apiece and fit in the palm of your hand, can accurately detect small amounts of fentanyl in a sample—information that can save lives.

“We are at a pivotal moment,” says study lead author Susan Sherman, PhD ’00, MPH, a professor in Health, Behavior and Society. “We are going to continue to watch these numbers of fentanyl deaths go up without an end in sight, or we’re going to open our minds about how we can actually save lives, and fentanyl checking is a proven way to do that.”

The study’s survey of 355 people who use street drugs in Baltimore, Boston and Providence, Rhode Island, shows that the overwhelming majority supports use of the strips to prevent overdoses. So do drug treatment professionals, outreach workers and patient advocates.

FORECAST also assessed two other fentanyl-detecting technologies. The Bruker ALPHA machine accurately detected fentanyl, but it costs $20,000 and requires a trained operator. A second machine, TruNarc, showed low sensitivity to fentanyl, so researchers did not recommend its use.

PhD candidate and study co-author Ju Park, MHS ’13, says researchers hope the study leads to greater distribution of fentanyl test strips by health departments, nonprofits and others who work with opioid users.

“With an illegal drug market, there is typically no way for users to know what they are using,” Park says.